Most investors – at some time – will be either tempted to time when to be in or out of equity markets – or wish they had when markets fall. It would be great to be able to capture the upsides and avoid the downsides, but that is wishful thinking.

Investors may well underestimate the rapidity and magnitude of the movements that markets make, although the very material double digit daily moves around the Covid- crisis (March 2020) provided a useful lesson. In fact, a small number of days account for much of the market movement over time. Picking which those days are – either to be in or out of the markets – is an extremely difficult prospect and the chances of long-term success are rare. An analysis of missing the best days in the market (Albion, 2023) provides some food for thought, as the figure below illustrates.

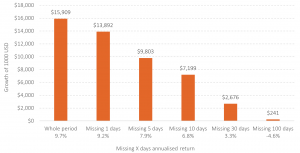

Figure 1: Missing the best few days in the markets could be very costly

Source: Albion Strategic Consulting.

Data: Morningstar Direct © All rights reserved: SSgA SPDR ETF. Returns in USD. 23/01/1993 – 30/01/2023

Whilst these types of study imply a binary approach to being invested in equities or cash, which is a somewhat unreal scenario, it is evident that a few good days, weeks or months drive the bulk of market returns and missing them can be costly. Missing the best 30 days in this 30-year period deliver only 17% of the rewards that the market delivered[1].

Likewise missing the worst 30 days would be highly beneficial, yet the ability to pick them does not seem to show up in the data. The October 2022 Liz Truss/Kwasi Kwarteng ‘mini-budget’ in the UK provided evidence of just how quickly new information can impact markets, in that case the bond market. Being right is quite a challenge. Being wrong can be very costly. The odds of success in market timing are slim.

A seminal piece of UK research (Cuthbertson et al., 2006) concluded that only around 1.5 % of UK equity funds demonstrate positive market timing ability. The Nobel Laureate Professor William Sharpe agrees:

‘An [investor] who keeps assets in stocks at all times is like an optimistic market timer. His actions are consistent with a policy of predicting a good year every year. While such a manager may know that such predictions will be wrong roughly one year out of three, such an attitude is nonetheless likely to lead to results superior to those achieved by most active market timers.’

Stay invested!

[1] As an aside, the data used is from the first US ETF launched thirty years ago, almost to the day. It was revolutionary at the time for providing cheap and tradable (not necessarily a good thing!) access to the S&P500 index.

Recent Comments