For decades, individuals have had a deep-rooted obsession with property, often viewing buy-to-let investments as a surefire path to wealth. However, the reality of managing such properties, with its financial and emotional burdens, may not be as straightforward as it seems. While many have profited from buy-to-let, much of this success is attributed to timing and luck. Meanwhile, the media has often perpetuated the notion that pensions are ineffective, overshadowing their importance in retirement planning.

Buy-to-let investments can seem appealing due to their tangible nature and the familiarity of managing mortgage debt, often perceived as less risky. Stories of success abound, though they rarely highlight the associated stress and failures. The allure of strong gross rental yields, driven by factors like a growing population and low supply, can be misleading.

Conversely, pensions have faced criticism, partly due to past mis-selling scandals, even though they offer significant tax benefits and a stable investment environment. Despite perceptions, sensible investing involves diversifying across global markets, which have historically provided substantial returns above inflation. The same cannot be said for broad residential property markets as we explore below.

Some investors see buy-to-let as an alternative to cash deposits, especially with relatively low deposit rates and inflation eroding the value of savings by over 20% in the past 20 years[1]. The search for higher yields has driven many towards riskier investments like high-yield bonds and equities, or into the buy-to-let market. However, transitioning from cash to buy-to-let is not a minor risk adjustment but a significant leap, especially if borrowing is involved. Entering the buy-to-let market essentially means starting a highly leveraged business with all its associated costs, taxes, and risks. Without thorough planning and realistic expectations, investors may face substantial financial challenges.

Few investors would consider borrowing up to three times the value of their investment portfolio to gear up their stocks and bond assets yet buy-to-let investors often do just that. Property investing allows for easy leverage, with most buy-to-let mortgages requiring a 25% deposit. For example, a £200,000 house might involve a £50,000 deposit and £150,000 loan. This leverage can amplify both gains and losses; a 20% property price increase yields an 80% return on the invested capital, while a 20% decline results in an 80% loss. Borrowing to leverage capital carries substantial risks, including the potential for negative equity. Historically, UK residential property values have fallen by around 30% after inflation during major downturns in 1989 and 2007.

Many investors, especially those new to the buy-to-let market, are attracted by the gross yields which currently sit at around 6%. Average rental income is approximately £1,300 per month, implying an average property value of about £260,000[2]. However, the costs associated with buy-to-let investments are significant and come in three stages: initial purchase and setup, ongoing costs, and sale costs. Initial costs include stamp duty, professional fees, repairs, and certifications. Ongoing costs cover annual expenses like insurance, maintenance, and potential void periods, as well as longer-term costs for major repairs and replacements. Investors should budget around 30% to 35% of the gross income for these ongoing costs[3], excluding mortgage repayments. Any remaining income is taxed at the investor’s marginal rate, with a 20% tax credit on mortgage interest available since 2020. Finally, sale costs include agent fees and capital gains tax, unless the property is deemed a primary residence for a certain period.

When basic numbers are calculated, the true net yield of buy-to-let investments is far less compelling than headlines suggest. High property prices combined with ongoing and borrowing costs make it challenging for landlords to achieve worthwhile net yields. Using the 30% to 35% rule above and current mortgage rates, net yields can quickly fall to the 2% and below range, particularly when one assumes that the property may not be occupied 100% of the time if tenants choose to leave and cannot be replaced immediately.

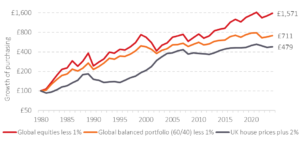

Lower yields make property price rises all the more important for buy-to-let property owners. An astute investor evaluates an asset class based on total return, combining yield and capital gain. By assuming a generous 2% net post-tax yield on an ungeared buy-to-let investment and adding it to the UK house price series, we can compare its performance against traditional investment portfolios. For fairness, a 1% annual cost is deducted from traditional portfolios, but no initial set-up costs are deducted from the buy-to-let strategy, even though they can be significant.

Figure 1: Buy-to-let versus traditional portfolios – simulated strategies after inflation 1981-2024

Data source: See endnote[4].

Pension funds are a core retirement pillar. Buy-to-let property is akin to owning a small business with a depreciating asset that requires constant attention to achieve returns somewhere between bonds and equities. Borrowing amplifies both risks and rewards, making it a significant leap from the deposit-like alternative often portrayed in the media. Buy-to-let is not a quick or riskless path to wealth; it involves substantial costs and demands meticulous management. In contrast, harnessing tax breaks and investing in a well-structured, globally diversified portfolio is a sensible approach to retirement planning, freeing up time for more enriching activities than managing rental properties.

Important Notes

This is a purely educational document to discuss some general investment related issues. It does not in any way constitute investment advice or arranging investments. It is for information purposes only; any information contained within them is the opinion of the authors, which can change without notice. Past financial performance is no guarantee of future results.

Products Referred to in this Document

Where specific products are referred to in this document, it is solely to provide educational insight into the topic being discussed. Any analysis undertaken does not represent due diligence on or recommendation of any product under any circumstances and should not be construed as such.

[1] Bank of England © SONIA and UK CPI. Data to Apr-25.

[2] ONS © Private rent and house prices, UK: April 2025.

[3] Before it was merged with other financial bodies in 2017, the Council of Mortgage Lenders (CML) advised holding back 30-35% of rental income to service ongoing costs.

[4] Global equities Albion World Stock Market Index (AWSMI). Balanced (60/40) = 60% ‘Global equities’, 40% Albion 2.5Y UK Constant Maturity Bond Index. Costs of 1% have been deducted from the ‘traditional’ portfolios and portfolios were rebalanced back to the original mix once a year. UK house prices = Nationwide House Price Index.

Recent Comments