Charlie Munger, the lifetime business partner of Warren Buffett at Berkshire Hathaway, passed away in late November at the ripe old age of 99. He was a deep thinker about business, who focused on the fundamental strengths of companies exhibiting a simplicity that he could understand. Although he was less high profile than Warren Buffett, he is credited with changing Buffet’s approach of buying ‘fair companies at wonderful prices’ to buying ‘wonderful companies at fair prices’.

He and Buffett delivered investors with stellar returns of +10% above the S&P500 index (1964-2022) [1], although the past two decades have been far more challenging, delivering the return of the market. He amassed great personal wealth through the investment returns of Berkshire Hathaway [2] – compounded over a long period of time – but gave the majority of it away to philanthropic works. In tribute, we look at a number of his well-known quotes.

Make yourself into the person you want to be.

A key driver of his personal philosophy was deciding on the person you want to be and then making sure that you become that person. He summed this up nicely as follows.

Early on, write your desired obituary — and then behave accordingly.

He was also focused on lifelong learning. He and Buffet both read voraciously every day and set aside time for thinking as opposed to doing. His advice was to go to bed smarter than when you woke up.

His thoughts on investing

His take on investing was that it was a long-term game where you make your choices, have the courage of your convictions, stick with it through thick and thin, and reap the rewards of time and compounding, avoiding emotional and financial costs along the way. Sounds familiar!

A lot of people with high IQs are terrible investors because they’ve got terrible temperaments. And that is why we say that having a certain kind of temperament is more important than brains. You need to keep raw irrational emotion under control. You need patience and discipline and an ability to take losses and adversity without going crazy. You need an ability to not be driven crazy by extreme success.

(Charles T. Munger, Value Investing: A Value Investor’s Journey Through the Unknown.)

Understanding both the power of compound interest and the difficulty of getting it is the heart and soul of understanding a lot of things.

(Poor Charlie’s Almanack)

His reference to ‘getting it’ includes financial and emotional cost leakage, not least chasing returns and trying to time markets, instead of sticking to a well-thought-out strategy.

When he and Buffet began their relationship at Berkshire in the 1960s the investing world was very different, with many more retail investors and fewer sophisticated institutional investors.

There is so much money now in the hands of so many smart people all trying to outsmart one another. It’s a radically different world from the world we started in.

(2023 Berkshire Hathaway Annual Meeting)

The implication is that markets are probably more efficient, meaning that bargains are far rarer for active managers. Berkshire’s size, and the greater efficiency of markets, has probably underpinned their more lackluster performance in the past two decades.

Even back in 1994, he saw that the investment management industry had become a factory churning out glistening products that appealed to the investment magpies, particularly faddish products designed to chase yesterday’s returns.

I think the reason why we got into such idiocy in investment management is best illustrated by a story that I tell about the guy who sold fishing tackle. I asked him, ‘My God, they’re purple and green. Do fish really take these lures?’ And he said, ‘Mister, I don’t sell fish.’

(A Lesson on Elementary, Worldly Wisdom as It Relates To Investment Management & Business, 1994 speech at USC Business School)

Today, there are over three million (yes, that is correct!) indices available to investors and more equity mutual funds available than there are listed companies in the world. This is the ‘idiocy’ to which he refers. In reality, a sensible, systematic approach to investing requires only a handful of funds to capture market exposures and make evidence-based, long-term risk factor tilts.

One fundamental difference between Charlie Munger’s approach to investment and that of a systematic investor relates to diversification.

The worshipping at the altar of diversification, I think that is really crazy…I find it much easier to find four or five investments where I have a pretty reasonable chance of being right that they’re way above average. I think it’s much easier to find five than it is to find 100. I think the people who argue for all this diversification — by the way, I call it ‘diworsification’ — which I copied from somebody — and I’m way more comfortable owning two or three stocks which I think I know something about and where I think I have an advantage.

(2021 Daily Journal Annual Meeting [3])

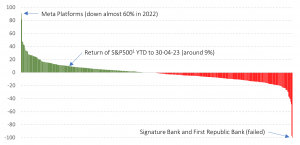

At one level he is right. Long-term market returns are driven by just a handful of stocks. Research suggest that around 4% of US companies have driven all of the returns of the US market since 1926 [4]. At another level, for most investors he is probably not right, even if it was right for him. The challenge for investors is picking these stocks. Perhaps in a time when markets were less efficient and with two deep, investment obsessed investors working on the problem, then finding at least a few of these companies may have been possible. But for the vast majority of investors, the only way they can guarantee to pick these winning firms is to own the entire market. The cost of getting it wrong is too big to contemplate and few have the time, insight and fortitude to risk doing so. As his partner Warren Buffett once said:

By periodically investing in an index fund, for example, the know-nothing investor can actually out-perform most investment professionals. Paradoxically, when ‘dumb’ money acknowledges its limitations, it ceases to be dumb.

(Berkshire Hathaway shareholder letter 1993.)

Charlie Munger will be remembered as one of the great ‘active’ investors and a man of humility and integrity. People like him are few and far between.

Charlie Munger (1924-2023)

[1] https://www.berkshirehathaway.com/letters/2022ltr.pdf

[2] At the time of his death his shares in Berkshire Hathaway were worth US$2.6 billion but the records show that at one point he owned shares worth in excess of US$10 billion, sales of which have funded his philanthropic endeavours.

[3] The newspaper publishing company he chaired from 1977 through 2022

[4] Bessembinder, H. (2018) Do stocks outperform Treasury bills? Journal of Financial. Economics, vol. 129, no. 3, 440–457. https://doi.org/10.1016/J.JFINECO.2018.06.004

If you have any questions or queries about anything in relation to the nature of this blogpost, you can contact info@pacem-advisory.com.

Recent Comments